Going Public: How Are Direct Listings Different from IPOs?

An initial public offering (IPO) is the first public sale of stock shares by a private company. IPOs are important to the financial markets because they help fuel the growth of innovative young companies and add new stocks to the pool of potential investment opportunities.

When a company files for an IPO, new shares are created, underwritten by a bank, and sold to the public. But that's not the only way for a company's stock to become publicly traded. When a company uses a direct listing, typically only existing shares are sold to the public on a stock exchange — no new shares are issued, and no underwriters are involved.

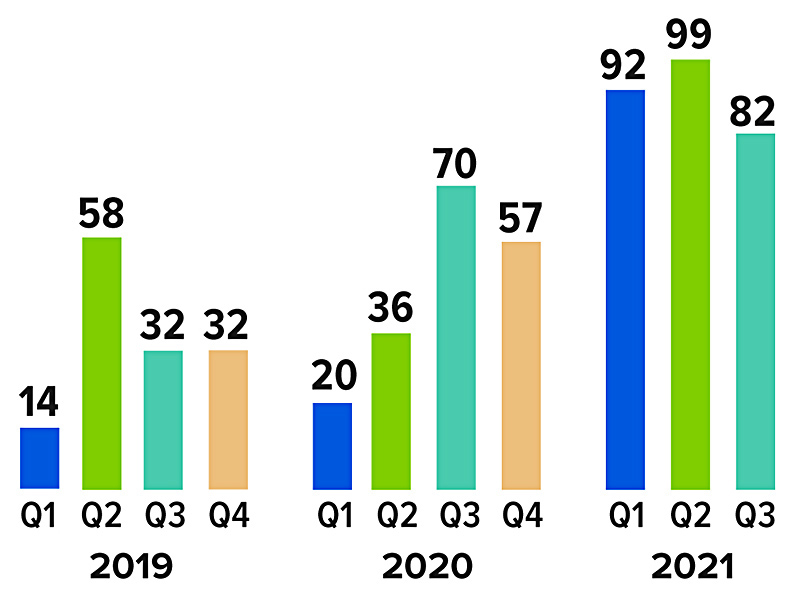

There were more U.S. IPOs in the first half of 2021 than there were in all of 2020, which was also a record year.1 The number of direct listings has ticked up, too, but there were just three in 2020 and six in 2021.2

Going public is a fraught process that few companies dare to navigate on their own. Even so, several well-known companies have sparked media coverage and investor curiosity when they chose to bypass the traditional IPO process.

Two Roads, One Less Traveled

The path a company takes to the stock market generally depends on its business goals. Companies that pursue a traditional IPO often want to raise as much money as possible for expansion purposes. Direct listings, on the other hand, give company founders, employees, and early investors a way to cash out some of their equity without diluting the value of the company's stock.

The underwriters that facilitate the IPO process typically organize a "roadshow" to market the stock and gauge the interest of institutional investors. They also guide the company through regulatory requirements, help set the initial offer price, and may guarantee the sale of a specified number of shares at the offering price. IPOs usually have a three- to six-month lockup period, which is an agreement with underwriters that prevents employees and other early investors from immediately selling their shares. Keeping insider shares off the market can help quell market volatility in the early days of trading.

A company may be able to make its stock market debut faster and at a much lower cost with a direct listing, and there is no lockup period. But going public without underwriting support can also be risky. The supply of shares becoming available for sale is undefined, and the demand for those shares can be difficult to predict, which could result in insufficient liquidity.

Number of Traditional U.S. IPOs

Source: PwC, 2021

Investor Access

One catch associated with IPOs is that many investors who want to buy shares at the offering price don't have the opportunity to do so. Moreover, those who buy the stock on the first day of trading often miss out on much of the soughtafter "pop," because a large part of the appreciation can take place between its pricing and the first stock trade. With a direct listing, everyone has access to the stock at the same time, but this also means share prices can be more volatile after trading begins.

In fact, some investors who rush to buy highly anticipated IPOs or directly listed stocks on the first day might pay inflated prices, because that's when media coverage, public interest, and demand may be greatest. Share prices could drop in the weeks following a large first-day gain as the excitement dies down and fundamental performance measures such as revenues and profits take center stage.

The return and principal value of all stocks fluctuate with changes in market conditions. Shares, when sold, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Investments offering the potential for higher rates of return also involve a higher degree of risk.